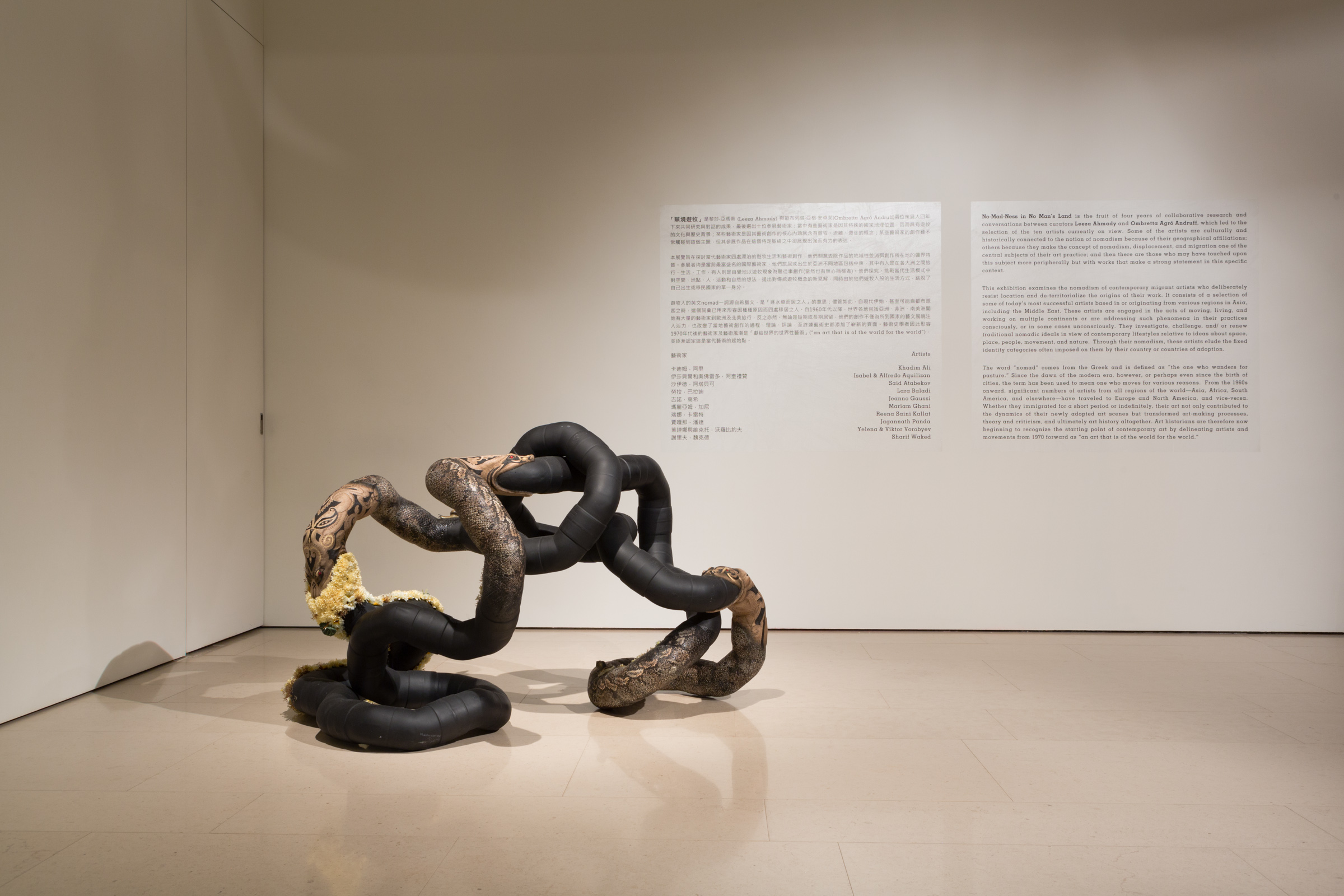

No-Mad-ness in No Man's Land, Eslite Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan, November 9-December 22, 2013

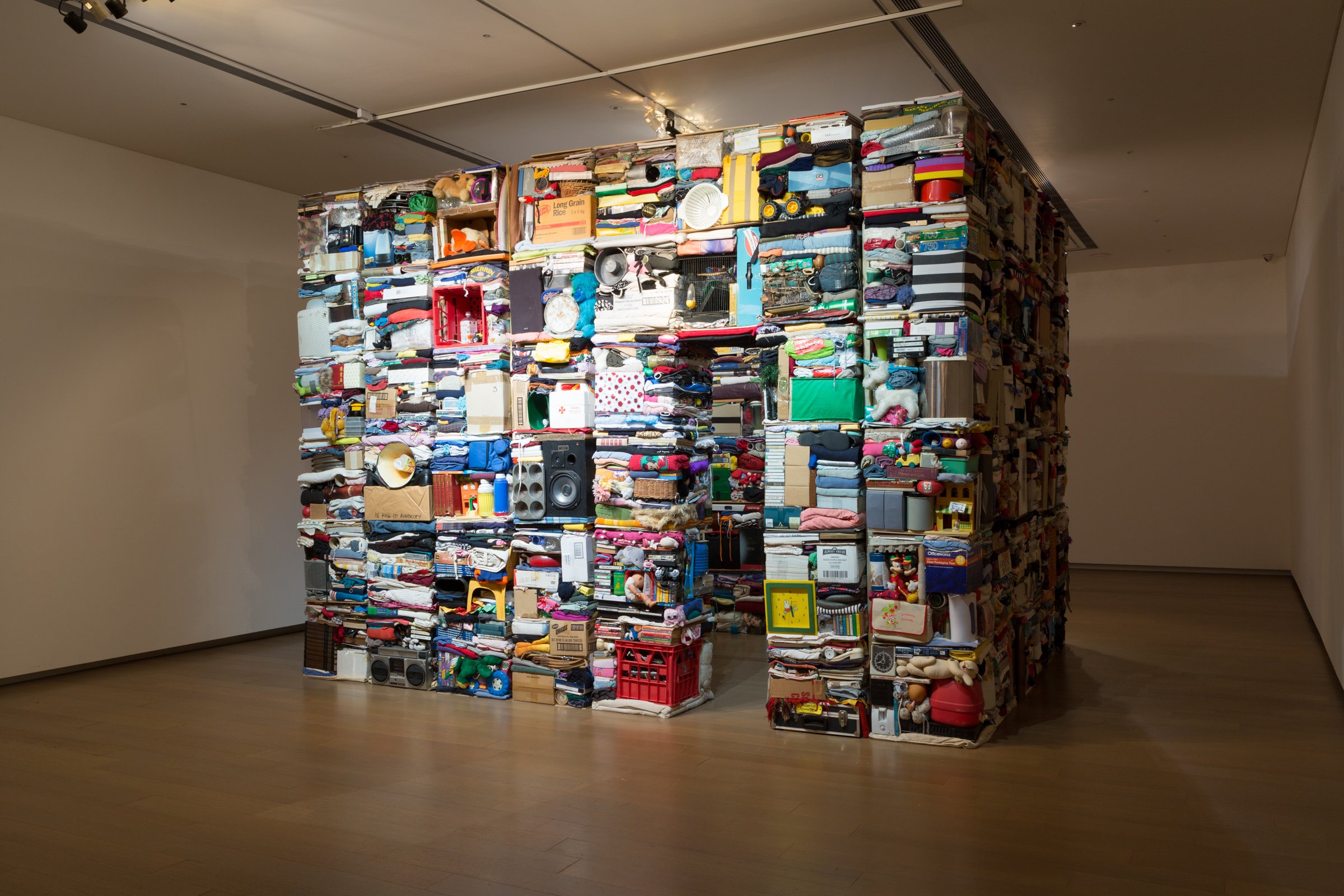

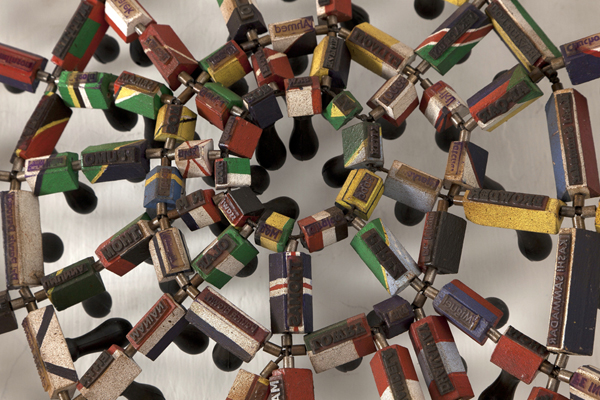

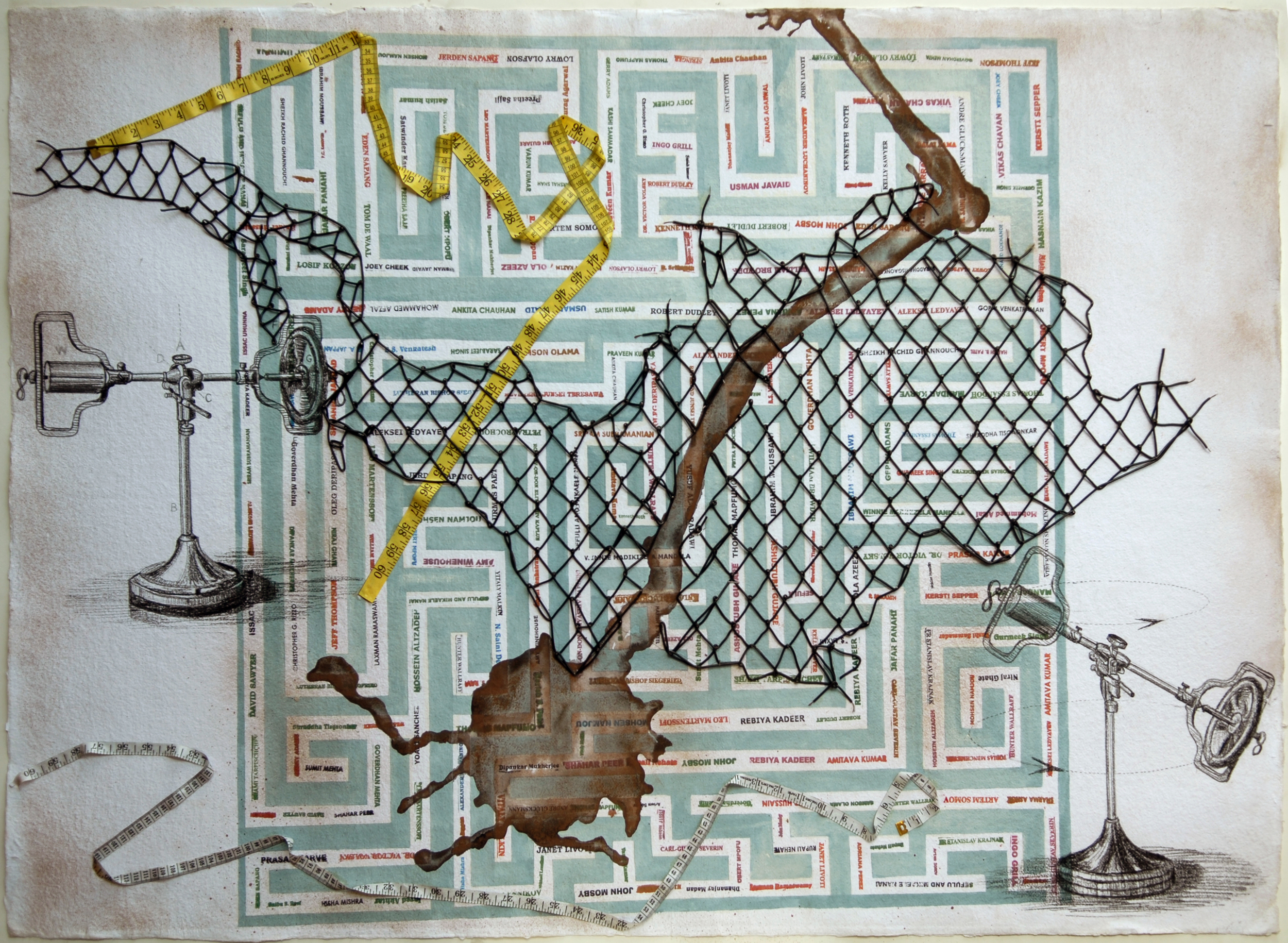

No-Mad-Ness in No Man’s Land is the fruit of four years of collaborative research and conversations between curators Leeza Ahmady and Ombretta Agró Andruff, which led to the selection of the ten artists currently on view. Some of the artists are culturally and historically connected to the notion of nomadism because of their geographical affiliations (Said Atabekov, Yelena Vorobyeva, and Viktor Vorobyev); others because they make the concept of nomadism, displacement, and migration one of the central subjects of their art practice (Mariam Ghani, Sharif Waked, Jeanno Gaussi, Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan, and to some extent Reena Kallat and Jagannath Panda); and than there are those who may have touched upon this subject more peripherally but with works that make a strong statement in this specific context (Lara Baladi and Khadim Ali).

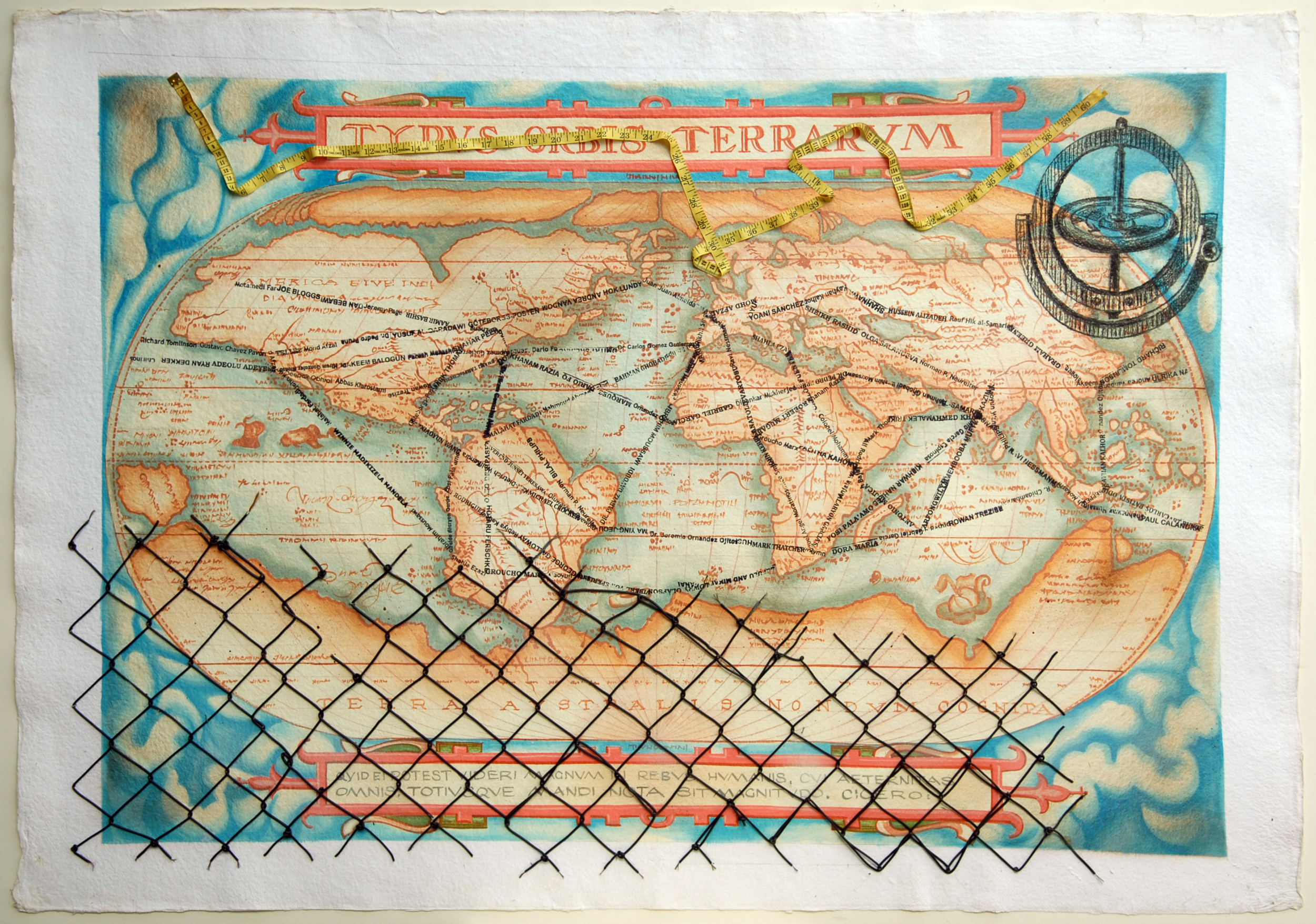

This exhibition examines the nomadism of contemporary migrant artists who deliberately resist location and de-territorialize the origins of their work. It consists of a selection of some of today’s most successful artists based in or originating from various regions in Asia, including the Middle East. These artists are engaged in the acts of moving, living, and working on multiple continents or are addressing such phenomena in their practices consciously, or in some cases unconsciously. They investigate, challenge, and/ or renew traditional nomadic ideals in view of contemporary lifestyles relative to ideas about space, place, people, movement, and nature. Through their nomadism, these artists elude the fixed identity categories often imposed on them by their country or countries of adoption.

The word “nomad” comes from the Greek and is defined as “the one who wanders for pasture.” Since the dawn of the modern era, however, or perhaps even since the birth of cities, the term has been used to mean one who moves for various reasons. From the 1960s onward, significant numbers of artists from all regions of the world—Asia, Africa, South America, and elsewhere—have traveled to Europe and North America, and vice-versa. Whether they immigrated for a short period or indefinitely, their art not only contributed to the dynamics of their newly adopted art scenes but transformed art-making processes, theory, and criticism, and ultimately art history altogether. Art historians are therefore now beginning to recognize the starting point of contemporary art by delineating artists and movements from 1970 forward as “an art that is of the world for the world.”